Server-side request forgery (SSRF)

Modern web applications often retrieve external resources, like images, documents, API responses, or webhook data, based on user input. When this functionality is not properly secured, it can introduce a serious vulnerability known as server-side request forgery.

SSRF allows an attacker to make the application’s server send unintended requests to internal or external systems. In cloud and microservices environments, this can expose sensitive data, internal networks, and even cloud credentials.

What is SSRF (server-side request forgery)?

Server-side request forgery (SSRF) is a web application security vulnerability that occurs when an application fetches a resource from a URL supplied by a user, and an attacker manipulates that URL to make the server send unauthorized requests.

Instead of only accessing intended external resources, the vulnerable server may send requests to internal services, localhost, private IP ranges, or cloud metadata endpoints. Because these requests originate from the server itself, they can bypass authentication, web application firewalls (WAFs), and network restrictions. In some cases, SSRF can expose internal resources, APIs, sensitive information, or cloud access credentials.

SSRF is classified as CWE-918.

How SSRF attacks work

At its core, SSRF exploits functionality that allows a server to fetch remote resources, as well as implicit trust in developer-supplied resource URLs.

Basic SSRF attack flow

Consider an application that lets users supply a URL to retrieve an image using a request like:

https://example.com/fetch?url=https://images.example.com/logo.png

The server retrieves the image from a subdomain and returns it to the user.

If the application does not validate and restrict the URL properly, an attacker could submit:

https://example.com/fetch?url=http://localhost/admin

Instead of retrieving an external image, the server now requests an internal administrative endpoint. Crucially, the access request originates from the web server, which may allow access to resources that are not publicly exposed.

Targeting internal services through SSRF

Common SSRF targets include:

http://localhost127.0.0.1- Private IP ranges such as

10.0.0.0/8or192.168.0.0/16 - Internal microservices and admin interfaces

In modern architectures, internal APIs often assume they are protected by network segmentation and thus only implement limited authentication or authorization controls. Successful SSRF breaks that assumption by using the application server as a proxy.

Exploiting SSRF to extract cloud metadata

In cloud environments, SSRF can be especially dangerous. Many cloud providers expose instance metadata services at reserved IP addresses. For example, in AWS:

http://169.254.169.254/latest/meta-data/

If an attacker can force the server to query this endpoint, they may retrieve temporary credentials associated with the instance, which can then be used to access cloud services and resources.

The 2019 Capital One breach is a well-known example of an SSRF vulnerability that, when combined with other misconfigurations, ultimately led to the exfiltration of many gigabytes of sensitive financial data from cloud buckets.

Example of a web application SSRF attack

The most typical example of SSRF is when the attacker can control the URL of a third-party service called by the application. The following vulnerable code was written to fetch a PNG image from an external URL and output it directly on the HTML page:

<?php

if (isset($_GET['url'])) {

$url = $_GET['url'];

$image = fopen($url, 'rb');

header("Content-Type: image/png");

fpassthru($image);

}

?>For this scenario, we’re assuming the attacker has full control of the url parameter and nothing in the configuration would prevent them from making arbitrary GET requests to any external or internal IP.

SSRF attack payloads

With this vulnerable application running on an Apache web server with mod_status enabled (the default configuration), an attacker can replace the image URL with a variety of SSRF payloads. They could start by sending a server status request:

GET /?url=http://localhost/server-status HTTP/1.1

This returns detailed information about the server version, installed modules, and more to find other vulnerabilities and attack points.

Apart from the typical http and https URL schemas, attackers might also use less common URL schemas in their payloads. The file schema could be one way to access files on the local system or the internal network.

GET /?url=file:///etc/passwd HTTP/1.1

This payload will provide the attacker with the content of the /etc/passwd file from the server hosting the vulnerable application.

Common SSRF types and variants

SSRF vulnerabilities manifest in different forms depending on application behavior, runtime architecture, and defensive controls.

Basic (non-blind) SSRF

In a full SSRF scenario, the attacker supplies a malicious URL and directly receives the server’s response. This makes exploitation straightforward because the retrieved data is returned immediately.

Blind SSRF

With blind SSRF, the attacker cannot see the response to their payload. Instead, they need to rely on side effects or out-of-band channels, such as:

- Triggering an outbound request to an attacker-controlled server

- Observing DNS interactions

- Measuring response timing differences

Blind SSRF is harder to perform but also to detect, and may require out-of-band techniques to confirm exploitation.

Restricted SSRF

In a restricted scenario, input validation and sanitization restrict certain patterns, but attackers can still bypass filters using encoding tricks, alternative IP representations, or redirect chains.

SSRF via XML external entities (XXE)

Insecure XML parsing can allow attackers to define external entities that cause server-side HTTP requests. This type of SSRF is closely related to XXE injection.

SSRF in APIs

Modern APIs often accept URLs for callbacks, integrations, or data ingestion. Poor API security practices can introduce SSRF risk even when no traditional web interface is involved.

SSRF vs CSRF

SSRF is often confused with the similarly named CSRF.

Cross-site request forgery (CSRF) exploits a web application’s failure to verify the origin of state-changing requests. A successful CSRF attack tricks a user’s browser into sending unintended requests using the victim’s authenticated session. In contrast, SSRF manipulates a server into sending such requests.

The client-side vs server-side distinction is crucial to understanding the difference in impact. CSRF typically affects a specific authenticated user session. SSRF, in contrast, can expose backend infrastructure and internal systems, potentially affecting the entire application environment.

Why SSRF still matters in 2026

SSRF remains highly relevant in cybersecurity because API-heavy application architectures increase the internal attack surface and potential data exposure.

Cloud-native environments rely heavily on internal APIs and metadata services. Microservices communicate over private networks, and serverless functions and containers often have implicit trust relationships.

Whenever SSRF allows access to these internal systems, attackers may be able to:

- Retrieve cloud credentials

- Access internal administrative panels

- Pivot to other services

- Exfiltrate sensitive data

- Perform port scanning on internal systems

Potential consequences of an SSRF attack

Apart from obtaining unauthorized access to privileged internal resources, attackers may also use SSRF to hide the actual source of the connection. For example, a hacker may use SSRF as an indirect attack route to cover their tracks and make forensics harder. In particular, they might use a vulnerable server as a proxy for further attacks on other systems – so if your server has an SSRF vulnerability, it may appear in logs as the attack source.

In the worst case, if SSRF is combined with other attack vectors such as RCE, XXE, XSS, CSRF, or SQL injection, it may allow attackers to access sensitive data or take full control of a vulnerable server. Here are two possible scenarios:

- SSRF with SQL injection: An attacker may use SSRF to gain access to a business-critical application on another server that should only be accessible from the internal network. If that application has a SQL injection vulnerability, they could extract or manipulate backend database data.

- SSRF with RCE: An attacker may use SSRF to gain access to an internal application that has a remote code execution (RCE) vulnerability. After obtaining RCE, they can get shell access and continue the attack on the internal server.

How to prevent SSRF

SSRF prevention requires both application-level and infrastructure-level controls applied in a combined and layered way.

Validate and allow-list URLs

Avoid accepting arbitrary URLs whenever possible. If remote resource fetching is required:

- Use strict allow-lists of approved domains

- Validate the full resolved hostname

- Avoid relying only on block-lists (blacklists) and filtering

- Block access to private (non-routable) IPs unless specifically required

Use secure response handling

If your application displays or processes data received from other servers, always make sure that the response you received is the expected content type and format before processing. Never send the raw response body to the client.

Note that this does not protect against blind SSRF attacks.

Disable unnecessary protocols

If your application only needs HTTP or HTTPS, explicitly block protocols like file://, ftp://, gopher://, etc. Restricting accepted protocols reduces the attack surface.

Enforce strict URL parsing

Normalize and validate user-supplied URLs before processing them:

- Prevent alternative IP encodings

- Reject unexpected schemes

- Disallow embedded credentials

Restrict outbound network access

Limit where application servers can send outbound requests to minimize SSRF opportunities:

- Block access to private IP ranges where not required

- Prevent access to metadata IP addresses

- Use firewall rules or service mesh policies

Protect cloud metadata endpoints

Lock down your cloud environments:

- Use modern metadata protections such as AWS IMDSv2

- Limit instance role permissions

- Avoid exposing overly permissive credentials

Monitor outbound traffic

Outbound traffic anomalies often provide early warning of SSRF exploitation. Log and monitor unexpected outbound requests and alert on potential SSRF signals like:

- Requests to

localhost - Requests to internal IP ranges

- Access attempts to metadata endpoints

How to mitigate SSRF vulnerabilities

Mitigating SSRF depends on where the vulnerability exists and whether a patch is available. Unlike prevention during development, mitigation focuses on reducing risk in already deployed systems.

Fix vulnerable custom applications

For internally developed software, the only permanent mitigation is to remove the root cause:

- Avoid using untrusted user input to construct outbound requests

- Implement strict allow-listing (whitelisting) and URL validation

- Restrict outbound network access from the application server

All other controls reduce risk but do not eliminate the underlying vulnerability.

Update vulnerable third-party software

If SSRF exists in a third-party product:

- Identify the affected version

- Review vendor security advisories

- Upgrade to a patched release as soon as possible

Vulnerable versions can often be identified using software composition analysis (SCA) or vendor advisories. Version management and timely patching are critical because SSRF flaws are often publicly documented once disclosed.

Apply temporary protections for zero-day SSRF

If no patch is available, you can reduce exposure with compensating controls:

- Deploy targeted WAF rules to block known exploit patterns

- Restrict access to internal IP ranges and metadata endpoints

- Limit outbound connections from the vulnerable service

These measures make exploitation more difficult but do not fix the root cause, so they should be treated as temporary safeguards.

Harden internal services to limit SSRF blast radius

SSRF mitigation should not focus only on the vulnerable application. Many internal services, such as Memcached, Redis, Elasticsearch, or MongoDB, run without authentication by default because they are assumed to be accessible only from trusted networks. If an attacker can exploit SSRF, those assumptions no longer hold.

To reduce the impact of a successful attack:

- Enable authentication on internal services

- Limit network exposure between services

- Apply least-privilege access controls

- Protect cloud metadata services and restrict role permissions

Even where SSRF cannot be fully prevented, hardening internal systems significantly reduces the damage an attacker can cause.

How security testing tools detect SSRF

Even with a solid combined approach to SSRF prevention, security testing is still a must. Static testing tools (SAST) can help with enforcing code-level safeguards, but because SSRF attacks exploit runtime behavior, SSRF vulnerabilities are hard to detect using static analysis alone.

Dynamic application security testing (DAST) tools simulate attacker behavior by injecting payloads into URL parameters and observing how the application responds. By interacting with the running application, DAST can identify cases where user input influences server-side requests.

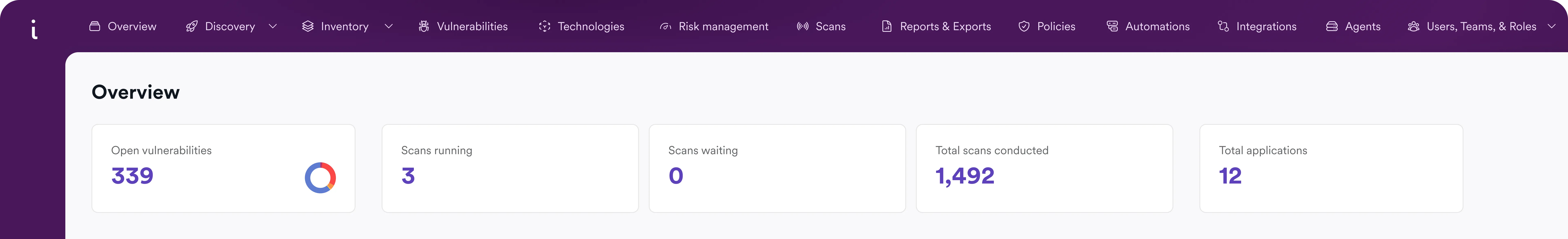

Modern solutions such as DAST on the Invicti Platform can also validate exploitability by confirming that the application can be induced to make unintended outbound requests and generating a proof of exploit. This runtime validation cuts down on false positives and allows security and development teams to focus on issues that represent real risk.

Request a demo to see how a unified, DAST-first approach helps security teams reduce noise, validate actual risk of SSRF, and prioritize remediation effectively.

Frequently asked questions

In full SSRF, the attacker can see the server’s response. In blind SSRF, the response is not visible, and the attacker must rely on indirect, out-of-band evidence such as DNS lookups or external callbacks to confirm exploitation.

Yes. If a vulnerable application can access cloud metadata services, an attacker may retrieve temporary credentials associated with the instance. Proper metadata protection and outbound filtering significantly reduce this risk.

Yes. SSRF was added as a distinct category in the OWASP Top 10 in 2021 due to its increasing prevalence and impact in cloud-native environments. In the 2025 edition, it is included within the top-ranked A01:2025 Broken Access Control category.

API endpoints that accept URLs for webhooks, callbacks, or data imports can introduce SSRF risk if inputs are not properly validated. As API usage increases, so does the potential attack surface for SSRF.

Organizations should combine secure coding practices, strict URL validation, outbound network controls, and continuous security testing. Runtime testing with DAST provides visibility into exploitable SSRF conditions in deployed applications.

Related Blog Posts: